The mother’s death gathers together the three brothers back to their youth home. Raffaele (Philip Noiret), the oldest, a successful famous judge, from Rome. Nicola (Michele Placido), a blue collar active in the union movement, dealing with his marriage crisis. Rocco, reserved and spontaneous, dedicated to help children in a correctional institute.

Donato, their father, a sweet old man, lined by a peasant life, simple and sincere. He called his boys for their mother’s funeral. So the three of them meet again after a long time in their old family house, where each one has something to recall.

We are in the south of Italy, in a dry flat infinite silent plateau. The house in white lime surrounded by the typical dry-stone walls. The faithful dog follows the old man around the desert courtyard. The windows are closed, because of the mourning. What a charming scene of solitude and sorrow, where feelings come out from things, and not from people. Even when we enter inside the room. The body is exposed to the care of the old black-dressed ladies who slowly and rhythmically repeat the proper litanies, with no interruption and no hesitation. A sound that is a melody, a melody that enchants and invites to indulge in ancient thoughts.

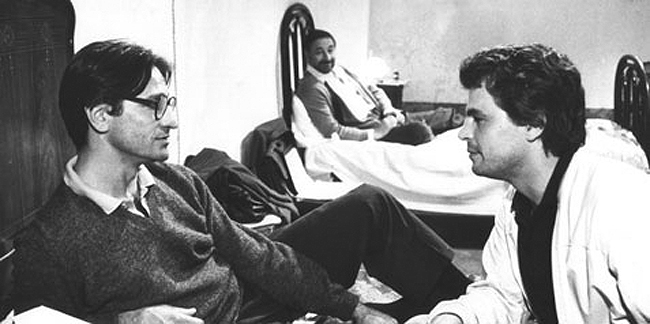

After quickly briefing about their lives, which is just an excuse for the director to introduce the nature of the characters, the three brothers reveal themselves during the night spent in the old large bedroom, with the light on, waiting for the funeral the morning after.

A moment of solitary, common meditation. An opportunity of comparison between who they were and who they are. An occasion of freedom, to face their fears or their wishes. With an awareness that is half way between the oneiric and the real.

But the dream of the father is different, it is the only dream that is about the past, real or not real, it is not important. He is with his young wife on the beach and suddenly, by playing with the sand she loses her wedding ring, Donato promises that they won’t leave without finding it, and the will. They find it. It’s a simple fact. The symbol of their simple love, their simple life. The only really important thing in their life, the promise of their love. How simple things were before.

A strong contrast with the ‘anni di piombo’ the years of terrorism, where young Italians are lost taking a political or a social position, culturally demanded to but intimately unprepared.

Well, the question is – like in the bar – do I have to be part of the social demand or I have to keep thinking about my private life? I don’t find an answer, as usual, but I do think that being part of a social movement, following a political ideal, is often a refuge to those who have lost their personal life track.

The final scene is the best. Donato, the old man, sees his wife’s wedding ring and slips it on his finger, next to his. Despite his loss, he seems relieved to have found himself back on track.

Find yourself wherever you are.