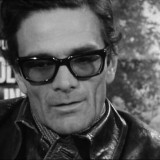

A lot has been written about Italy’s prominent, yet controversial film director, poet and journalist Pier Paolo Pasolini. This documentary film by Philo Bregstein offers a rare glimpse into the tumultuous life of Pasolini until his still unresolved murder circumstances in 1975.

A lot has been written about Italy’s prominent, yet controversial film director, poet and journalist Pier Paolo Pasolini. This documentary film by Philo Bregstein offers a rare glimpse into the tumultuous life of Pasolini until his still unresolved murder circumstances in 1975.

Rare, because the film was made six years after Pasolini’s death and so his memory is still fresh in the accounts of the people interviewed, which helps paint a much richer picture about the man, his background, personality, perspectives and the mystery behind his death.

The film showcases interviews with dignitaries such as Italy’s important poet Alberto Moravia that helps us place Pasolini’s in history. Moravia underscores his significance by talking about most poets before Pasolini came from the right and focused on aggrandizing Italy’s rich history. Pasolini was the first poet with left views that lamented the decline of Italian society, especially in the early 60’s where mass consumerism like television, he believed, contaminated the basic virtues of the simple people and their genuine cultures. That’s why Pasolini beyond being openly gay (a scandalous affair in those days), was attracted to the proletarians in the underworld of the Roman borgate. In this sense, Moravia believes Pasolini’s death was simply an accident that derives from his penchant for violent relationships as depicted in his two novels Ragazzi di vita (Boys of Life) and Una vita violenta (A Violent Life).

The film also brings actress Laura Betti (appeared in several of Pasolini’s films) that fought hard with the Italian justice system to find out what exactly happened that night. Her account suggests a reality that perceived Pasolini – because of his radical views and sexual preference – as a public threat and often times used him as scapegoat. He was brought to trial 33 times, yet acquitted every single time.

I especially liked the interview with renowned film director Bernardo Bertolucci that goes back to the early days of their friendship. Pasolini invited Betolucci to be his assistant in his first film Accatone, which tells the hardships of Pasolini’s friends – the boys from the Roman slums, but using his signature heroic ambiance. The way Betolucci tells it both he and Pasolini never had any cinematic experience, so every scene was practically an historic invention in the making. Betolucci poignantly concludes that Pasolini’s murder was probably some kind of crucifixion against a genius, caught in a wrong period. The film aptly ends with the heroic crucifixion scene in Pasolini’s The Gospel According To St. Matthew (1964).

Pasolini was murdered in 1975 by Giuseppe Pelosi, a 17-year-old hustler, which initially confessed for committing the crime. Yet, in 2005 he retracted his confession claiming that he was under threats to his family by three strangers with southern Italian accents who had committed the murder. The investigation was reopened, but then closed alleging the new elements as still insufficient.

And in Pasolini’s words:

“The mark which has dominated all my work is this longing for life, this sense of exclusion, which doesn’t lessen but augments this love of life.” (Interview in documentary, late 1960s)